As long as people work and live and play in the vicinity of North End Park in Boston, no winter will pass without someone recalling the catastrophe that took place there on January 15, 1919, just forty-six years ago.

The scene of this tragic accident was that low-lying section of Commercial Street between Copps Hill and the playground of North End Park.

Looking down from Copps Hill on that mild, winter afternoon, you saw first the tracks of the Boston elevatedóand the old, old houses nearby. Across the street were the freight sheds of the Boston and Worcester and Eastern Massachusetts Railways, the paving division of the Public Works Department, the headquarters of Fire Boat 31, and the wharves with patrol boats and minesweepers moored alongside. In the background to the left, the Charlestown Navy Yard. Towering above the freight sheds was the big tank of the United States Alcohol Companyóbulging with more than two million gallons of crude molasses.

In the Public Works Department, a dozen or more horses munched their oats and hay, as flocks of pigeons fluttered around to catch the stray kernels of grain that fell from the feed bags. Stretched out on the runningboard of a heavily laden express truck, ìPeter,î a pet tiger cat, slept in the unseasonably warm sunshine.

This was the fourth day that the mercury of the freight shed had been climbing. On the 12th of January it was only two degrees above zero. But, on the 13th, the temperature rose rapidly from sixteen degrees to forty; now, at 12:30 p.m. on Wednesday, the 15th, it was forty-three above zero, and so warm in the sun that office workers stood around in their shirtsleeves (talking about the weather). Even the freight handlers had doffed their overcoats, and sailors from the training ship Nantucket carried their heavy peajackets on their arms.

Mrs. Clougherty put her blankets out to air and smiled at little Maria Di Stasio gathering firewood under the freight cars. She waved to her neighbor, Mrs. OíBrien, planting her geraniums on a dingy window sill.

In the pumping station attached to the big molasses tank, Bill White turned the key in the lock and started uptown to meet his wife for lunch. He bumped into Eric Blair, driver for Wheelerís Express, and said, ìHello, Scotty. What are you doing around here at noontime? Thought you and the old nag always went to Charlestown for grub?î

The young Scotsman grinned, ìItís a funny thing, Bill. This is the first time in three years I ever brought my lunch over here;î and he climbed up on the bulkhead and leaned back against the warm side of the big molasses tankófor the first and last time.

Inside the Boston and Worcester freight terminal, Percy Smerage, the foreman, was checking a pile of express to be shipped to Framingham and Worcester. Four freight cars were already loaded. The fifth stood half empty on the spur track that ran past the molasses tank.

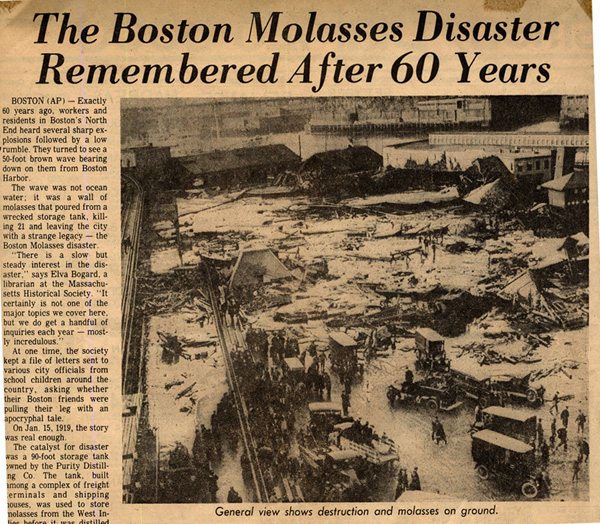

Smerage had just told his assistant to finish loading the last car when a low, deep rumble shook the freight yard. Then the earth heaved under their feet and they heard a sound of ripping and tearingósnipping of steel bolts (like a machine gun)ófollowed by a booming roar as the bottom of the giant molasses tank split wide open and a geyser of yellowish-brown fluid spouted into the sky, followed by a tidal wave of molasses.

With a horrible, hissing, sucking sound, it splashed in a curving arc straight across the street, crushing everything and everybody in its path.

Less time than it takes to tell it, molasses had filled the five-foot loading pit, and was creeping over the threshold of the warehouse door. The four loaded freight cars were washed like chips down the track. The half-loaded car was caught on the foaming crest of the eight-foot wave and, with unbelievable force, hurled through the corrugated iron walls of the terminal.

The freight house shook and shivered as the molasses outside, now five feet deep, pushed against the building. Then the doors and windows caved in, and a rushing-roaring river of molasses rolled like molten lava into the freight shed, knocking over the booths where freight clerks were checking their lists.

Like madmen they fought the on-rushing tide, trying to swim in the sticky stuff that sucked them down. Tons of freightóshoes, potatoesóbarrels and boxesótumbled and splashed on the frothy-foaming mass, now so heavy the floors gave way, letting tons of the stuff into the cellar. Down there the workers died like rats in a trap. Some tried to dash up the stairs but they slipped and fellóand disappeared.

As the fifty-eight-foot-high tank split wide open, more molasses poured out under a pressure of two tons per square foot. Men, women, children and animals were caught, hurled into the air, or dashed against freight cars only to fall back and sink from sight in the slowly moving mass.

High above the scene of disaster, an elevated train crowded with passengers whizzed by the crumbling tank just as the molasses broke loose, tearing off the whole front of the Clougherty house and snapping off the steel supports of the ìLî structure. That train had barely gone by when the trestle snapped and the tracks sagged almost to street level.

The roaring wall of death moved on. It struck the fire station, knocked it over on its side and pushed it toward the ocean until it fetched up on some pilings. One of the firemen was hurled through a partition. George Leahy, engineer of Fire Boat 31, was crushed to death under a billiard table.

In the Public Works Department, five men eating their noonday meal were smothered by the bubbling, boiling sludge that poured in upon them.

Up at fire headquarters, the first alarm came in at 12:40 p.m. As soon as Chief Peter McDonough learned the extent of the tragedy, he sounded a third alarm to get workers and rescue squads.

Ladders were placed over the wreckage and the firemen crawled out on them to pull the dead and dying from the molasses-drenched debris.

Amidst a mass of bedding and broken furniture, they found the body of Mrs. Cloughertyókilled when her house collapsed. Nearby lay the body of ìPeter.î

Capt. Krake of Engine 7 was leading his men cautiously along the slippery wreckage under the elevated when he saw a mass of yellow hair floating on a dark brown pool of molasses. He took off his coat and plunged his arms to the elbows in the sweet sticky stream. It was Maria Di Stasio, the little girl who had been gathering firewood.

Over by the Public Works Building, more than a dozen horses lay floundering in the molasses. Under an overturned express wagon was the body of the driver.

Fifteen dead were found before the sun went down that night and six other bodies were recovered later. As for the injured, they were taken by cars and wagons and ambulances to the Haymarket Relief and other hospitals.

The next day the firemen tackled the mess with a lot of fire hoses, washing the molasses off the buildings and wreckage and down the gutters. When hit by the salt water, the molasses frothed upóall yellow and sudsy. It was weeks before the devastated area was cleaned up.

Of course, there was great controversy as to the cause of the tankís collapse. And there were about 125 lawsuits filed against the United States Industrial Alcohol Company.

The trial (or rather the hearings) was the longest in the history of Massachusetts Courts. Judge Hitchcock appointed Col. Hugh W. Ogden to act as Auditor and hear the evidence. It was six years before he made his special report.

There were so many lawyers involved, that there wasnít room enough in the courthouse to hold them all, so they consolidated and chose two to represent the claimants.

Never in New England did so many engineers, metallurgists and scientists parade onto the witness stand. Albert L. Colby, an authority on the amount of structural strain a steel tank could sustain before breaking, was on the witness stand three weeksóoften giving testimony as late as ten oíclock in the evening.

Altogether, more than 3,000 witnesses were examined and nearly 45,000 pages of testimony and arguments were recorded. The defendants spent over $50,000 on expert witness fees, claiming the collapse was not due to a structural weakness but rather to a dynamite bomb.

When Auditor Ogden made his report, he found the defendants responsible for the disaster because the molasses tank, which was fifty-eight feet high and ninety feet across, was not strong enough to withstand the pressure of the 2,500,000 gallons it was designed to hold. In other words, the ìfactor of safetyî was not high enough.

And so the owners of the tank paid in all nearly a million dollars in damagesóand the great Molasses Case passed into history.

Thanks to Yankee Publishing for permission to reprint this article.